This guest blog post is part of a series written by Edward J. Farmer, PE, author of the new ISA book Detecting Leaks in Pipelines. To read all the posts in this series, scroll to the bottom of this post for the link archive.

My previous blog produced uncommon interest, some from old friends and some from persons newly engaged in struggling to preserve assets. One had experience with military operations in Iraq. They understood that theft is not just benign self-interest but may be conducted with the intent of deliberate harm.

Sometimes such operations disclose information about operator capabilities and requirements. Some deliberately embarrass the entities dedicated to preventing such incursions. Perhaps the message is that petroleum is valuable in many contexts and worthy of active care. In some locations and situations our confidence that the pipe we buried last year is still doing just what we intended may be unrealistically naïve.

Possibly the world leader in organized anti-theft effort is Pemex. Monitoring has been in-place on some of its systems for well over a decade and the results have been amazing. Initially some systems were looked at more as free distribution points where “the people’s petroleum” was delivered. Of course, that was never quite the intent, and there are many stories. This year, some estimates put Pemex losses to theft at over USD$1.5 billion. Applying its highly successful aggressive monitoring and interdiction program could, based on actual experience, eliminate most or even all of those losses.

Uncontrolled losses from pipelines - be it from accidents, equipment failures, or theft - is not a benign irritation. It can dramatically affect profitable operations and the sustained interest of investors. It can damage livestock and crops. It can initiate unimaginably intense fires and explosions that destroy lives, homes, and businesses along the pipeline. Surrounding businesses, such as fishing and agriculture, can be profoundly affected. Sometimes the damage is truly accidental, sometimes it is the result of poor design or changing operating conditions. Sometimes it results from inadequate maintenance practices such as corrosion control. In any case, the operator’s future may be improved or enhanced by responsible operation and aggressive mitigation. The public may be willing to excuse accidents but will often want to punish whatever they perceive as negligence.

The earliest anti-theft efforts began on lines known to be heavily attacked. Monitoring could detect a tap and its location within minutes. Special pre-positioned response units would be notified and would deploy into tactical positions. Usually the theft operation’s people and equipment could be apprehended. After a few such interdictions word got out. Theft from targeted areas declined to zero. Unfortunately, theft continued unabated in unmonitored areas. The prospect of getting caught diminished enthusiasm, but actual interdiction seemed necessary to completely discourage these operations.In some countries, enabled and exacerbated by corruption or government dysfunction, theft seems to have become normal. It can be hard to curtail these situations once they are firmly started. The spread of corruption seems systemic and the impact severe, not just from damages to the facilities and theft of the product of the producers, but also to the people and businesses that rely on normal access to these products. The fact the petroleum is stolen does not make it free to users – in fact the incursions can produce scarcity, increasing user-level cost.

In these matters, automation helps. Theft can, with appropriate effort, be curtailed or limited. Rational economic outcomes restore some sense of markets and order which tends to normalize and enhance business in the surrounding communities. The power and wealth associated with these activities can be limited or eliminated by fast and decisive action. Even sophisticated theft mechanisms can be identified by appropriate monitoring methods and equipment. Technology moves the endeavor from a conflict of wills to the effective use of resources.

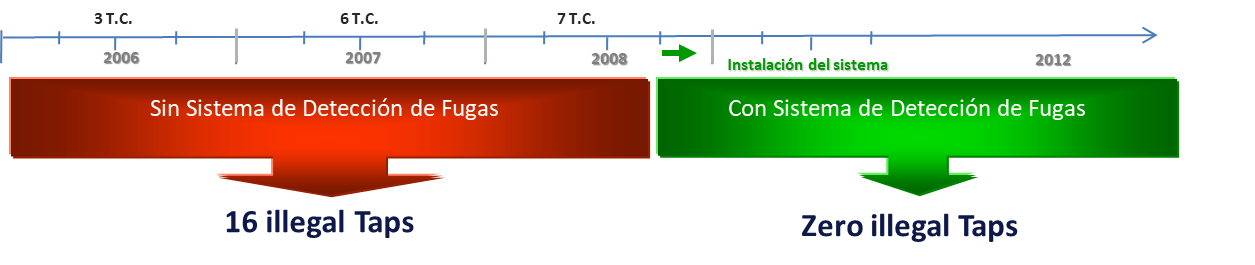

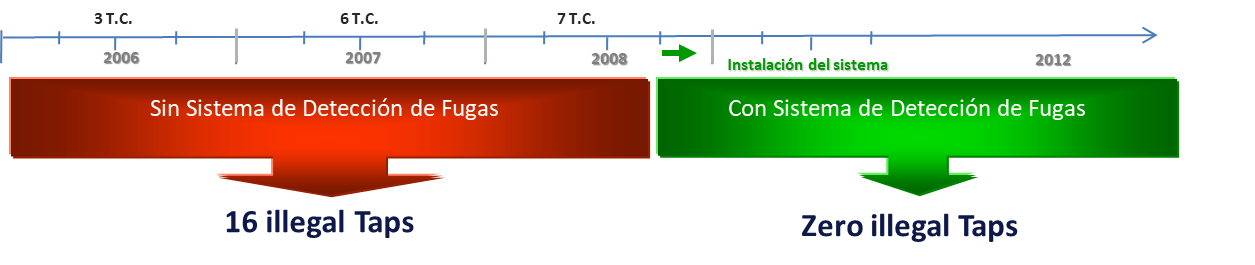

In one country, a pipeline that had been a substantial theft target was estimated to have perhaps 16 active theft taps at any given moment. Losses were in the many thousands of dollars per hour. A monitoring system was deployed, resulting in more than 20 apprehensions over the first few days. Theft attempts continued, but there were far fewer of them. Over a couple of months, theft on the entire pipeline was brought to, and maintained at, zero. Essentially, getting caught stealing oil involved sufficient consequences to concern these thieves, and the chance of getting caught was perceived to be very high. Together, these issues made theft an unattractively expensive activity.

So, technology, along with a determined and ethical attitude, can control these things. It isn’t even all that hard once it is productively organized and initiated. Safety is enhanced. Profitability is enhanced, security along the pipeline is enhanced, and business strength in the region improves – all good things for a successful and organized society.

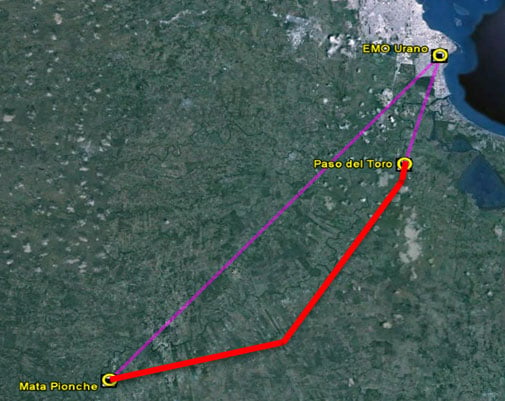

In this situation, as is often the case, the pipeline crossed a substantial distance covered by a double-canopy forest. People living in the region had long ago discovered the value of the product in the pipeline both for their own use and as a product that could be sold or traded to others. Even with air surveillance it was difficult for the operator to observe the alignment. Roads in and out of the pipeline alignment were available and well known. The monitoring program amounted to detecting the occurrence and location of a leak, transmitting the data to a rapid response force, and then monitoring the progress of the withdrawal until the response team arrived. If the withdrawal terminated early, the response team and their equipment could be re-routed to an exit-way. The results of the project, before and after the onset of monitoring, are shown in the graphic below.

In this situation, as is often the case, the pipeline crossed a substantial distance covered by a double-canopy forest. People living in the region had long ago discovered the value of the product in the pipeline both for their own use and as a product that could be sold or traded to others. Even with air surveillance it was difficult for the operator to observe the alignment. Roads in and out of the pipeline alignment were available and well known. The monitoring program amounted to detecting the occurrence and location of a leak, transmitting the data to a rapid response force, and then monitoring the progress of the withdrawal until the response team arrived. If the withdrawal terminated early, the response team and their equipment could be re-routed to an exit-way. The results of the project, before and after the onset of monitoring, are shown in the graphic below.

Uncontrolled losses from pipelines - be it from accidents, equipment failures, or theft - is not a benign irritation. It can dramatically affect profitable operations and the sustained interest of investors. It can damage livestock and crops. It can initiate unimaginably intense fires and explosions that destroy lives, homes, and businesses along the pipeline. Surrounding businesses, such as fishing and agriculture, can be profoundly affected. Sometimes the damage is truly accidental, sometimes it is the result of poor design or changing operating conditions. Sometimes it results from inadequate maintenance practices such as corrosion control. In any case, the operator’s future may be improved or enhanced by responsible operation and aggressive mitigation. The public may be willing to excuse accidents but will often want to punish whatever they perceive as negligence.

How to Optimize Pipeline Leak Detection: Focus on Design, Equipment and Insightful Operating Practices

What You Can Learn About Pipeline Leaks From Government Statistics

Is Theft the New Frontier for Process Control Equipment?

What Is the Impact of Theft, Accidents, and Natural Losses From Pipelines?

Can Risk Analysis Really Be Reduced to a Simple Procedure?

Do Government Pipeline Regulations Improve Safety?

What Are the Performance Measures for Pipeline Leak Detection?

What Observations Improve Specificity in Pipeline Leak Detection?

Three Decades of Life with Pipeline Leak Detection

How to Test and Validate a Pipeline Leak Detection System

Does Instrument Placement Matter in Dynamic Process Control?

Condition-Dependent Conundrum: How to Obtain Accurate Measurement in the Process Industries

Are Pipeline Leaks Deterministic or Stochastic?

How Differing Conditions Impact the Validity of Industrial Pipeline Monitoring and Leak Detection Assumptions

How Does Heat Transfer Affect Operation of Your Natural Gas or Crude Oil Pipeline?

Why You Must Factor Maintenance Into the Cost of Any Industrial System

Raw Beginnings: The Evolution of Offshore Oil Industry Pipeline Safety

How Long Does It Take to Detect a Leak on an Oil or Gas Pipeline?

Book Excerpt + Author Q&A: Detecting Leaks in Pipelines

About the Author

Edward Farmer has more than 40 years of experience in the “high tech” part of the oil industry. He originally graduated with a bachelor of science degree in electrical engineering from California State University, Chico, where he also completed the master’s program in physical science. Over the years, Edward has designed SCADA hardware and software, practiced and written extensively about process control technology, and has worked extensively in pipeline leak detection. He is the inventor of the Pressure Point Analysis® leak detection system as well as the Locator® high-accuracy, low-bandwidth leak location system. He is a Registered Professional Engineer in five states and has worked on a broad scope of projects worldwide. His work has produced three books, numerous articles, and four patents. Edward has also worked extensively in military communications where he has authored many papers for military publications and participated in the development and evaluation of two radio antennas currently in U.S. inventory. He is a graduate of the U.S. Marine Corps Command and Staff College. He is the owner and president of EFA Technologies, Inc., manufacturer of the LeakNet family of pipeline leak detection products.