This post was authored by Paul J. Galeski, CEO and founder of MAVERICK Technologies, a Rockwell Automation company.

Most companies outsource some portion of their project or engineering service needs, because fewer and fewer are fully self-sufficient. Invariably a manufacturer has to decide which elements of the business are critical enough to require internal execution, against those either generic enough to pass to someone else or specialized to a degree that require outside help.

Success in carrying out such a selection depends on understanding one’s own internal strengths, weaknesses, and business requirements. Once this is done and agreed upon internally, then the nature of the owner-supplier relationship can be developed to implement optimal engagement.

Some relationships are very straightforward:

- A machine shop may send parts for specialized processing that cannot be done practically or economically in-house, such as electropolishing.

- A chemical company might use a custom packager to meet specialized owner demand, such as delivering acetone in gallon cans rather than drums.

This discussion focuses on a more specialized kind of relationship common to process industries, where the outsourcing company is typically the owner of a plant or facility, and the supplier is a provider of automation solutions, as an example. Although the owner ultimately controls the purse strings and thus has more power than the supplier, the best relationships are those where both parties benefit mutually by giving and receiving the highest value services.

How does a supplier deliver value?

To update the old saying, if you want something done efficiently and effectively, maybe you should not do it yourself. The bulk of any company’s effort should be directed toward developing core strategic skills that cannot be effectively purchased outside. Keep in mind:

- Your company cannot be good at everything.

- Assess your internal strengths and weaknesses objectively, even if it means stepping on some toes. Understand what activities truly create a competitive advantage in your industry.

- Concentrate your valuable internal resources on the most strategic tasks related to your continued business and outsource the rest.

- Some functions are better left to experts, just like income taxes. Your needs are best served by hiring people who spend their professional lives working in that specialty.

Engineering is complicated, and relationships with automation solution providers can quickly become very complex. In many respects, increasing the distance between two partners increases complexity and workload, because every detail has to be spelled out and managed. When two organizations have a deeper understanding of each other, projects can become simpler. Everyone knows what to do, and each trusts the other to carry out its part without excessive supervision.

A supplier delivers the most value when a project is carried out in a manner requiring the least management on the owner’s end. But this means the supplier has to have a deep enough understanding of the owner to understand just what is wanted. This requires overcoming cultural differences between the process plant owner and the automation solution provider.

Projects drive relationships

Forming more complex relationships depends on the nature of the project and the need and desire to work together for the long term. Deep and longstanding relationships can be built around relatively small projects, and large projects do not necessarily ensure good relationships.

Various terms and acronyms describe these deeper relationships, including engineering procurement contractor (EPC), main automation contractor (MAC), and main enterprise partner (MEP). The definitions are not absolute, and common use causes them to overlap in various contexts. Moreover, the nature of a relationship can evolve from project to project, even when the parties stay the same.

Instead of trying to nail down a specific difference between a MAC and MEP, it is more useful to consider the kinds of relationships two parties can have. Each situation is unique, but much is determined by how the two parties view each other. The spectrum of possible relationships is quite wide, but can be divided into three basic categories:

Episodic but arms length—After working on a project or two, the supplier and owner begin to develop a general sense of mutual comfort. Individuals on both sides get to know their opposite numbers and learn the best methods of contact, what they can expect for response time, typical follow up on questions, and so on. Characteristics of this relationship include:

- Integrator manages the project and provides centralized responsibility.

- Owner may still obtain quotes from other integrators to “keep everyone honest.”

- Relationship can last for multiple projects out of a sense of convenience.

- Each project is still considered one-off, and any project may be the last because there is not a strong sense of commitment.

Basic sense of partnership—When a supplier is willing to extend itself for the benefit of the owner without needing to be coaxed, a partnership is forming. From the other side, the owner is willing to accept the supplier’s advice rather than insisting on its own way. Overall, trust is beginning to grow:

- The partnership requires work upfront to define needs and expectations.

- An ongoing relationship develops with a mutual sense of strategy for reaching the owner’s larger business objectives.

- Services cover all the needs for a project and can meet ongoing expectations after deployment.

- The relationship can reduce total cost of ownership by ensuring a higher level of standards and resource leverage.

Strong sense of partnership—When trust grows, each side wants to make sure the other is satisfied with every project and transaction. The owner receives the service expected, and the outcome of the project is more likely to meet performance, cost, and schedule targets. The integrator is paid fairly for the resources used with a reasonable profit level relative to the value provided. Such relationships do not happen overnight, and the integrator must have resources and infrastructure to deliver on its promises:

- Leadership on both sides must offer full support.

- The integrator must offer a complete suite of services capable of handling all technology needs.

- The ongoing relationship must be cultivated at all levels of both organizations, with shared strategies.

- The integrator must have resource depth to manage the owner’s entire technology spend.

- This approach should have the lowest total cost of ownership, but purchasing departments may find it scary at first.

How do you see your suppliers?

Given the above definitions, how do most process plant owners see their automation solution suppliers?

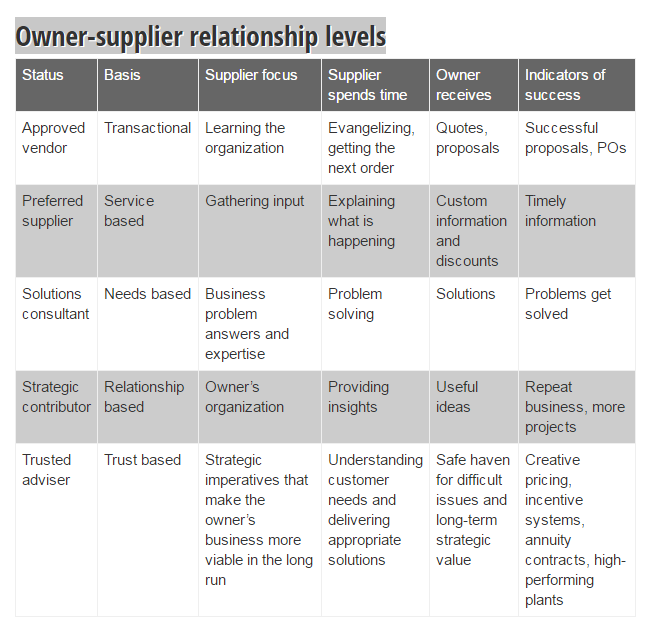

- Approved vendor—A company meets the most basic requirements to support transactions, but it has no specific desirability other than offering usable products and services. If the situation is appropriate, a transaction is permitted, but the supplier is always in a selling mode.

- Preferred supplier—An approved vendor with some desirability outside of its basic product offering, such as special pricing or commercial terms. Other things being equal, this company gets the order, but such relationships can be easily changed when a new supplier comes along with a better offer.

- Solutions consultant—A vendor or integrator offering ideas and solving problems in addition to basic products or services. The supplier has to feel there will be some appreciation for going above and beyond.

- Strategic contributor—At this level, the owner is beginning to depend on the provider as a source of strategic planning assistance. The relationship is moving beyond projects to broader-based challenges.

- Trusted adviser—This is the ultimate level of trust, where the provider and owner are partners, mutually considering the other’s position in a relationship. Both endeavor to ensure the long-term viability of the other, as well as mutual value and profitability in any transaction.

The table summarizes these stages of owner-supplier engagement and is a guide for identifying and improving upon existing relationships.

Choose your relationships wisely

Every supplier-owner relationship does not have the potential to advance to the trusted adviser level. Such relationships take time and a great deal of effort on both sides, so companies have to be selective. It is important to choose carefully and determine when such effort is in order:

- What kind of relationship with this owner or vendor is necessary to ensure the success of this project? Simple projects may only need simple relationships.

- Can you see yourself working with this company again? And again? If you do not see the potential or value a continuing relationship, do not waste your time.

- Do you trust each other? This is one of the most basic but potentially difficult questions, and it has to be answered without qualifications. “Maybe” does not work.

- Does the provider fit your culture? An extension of mutual trust includes shared values at all levels of the two organizations.

- Is this more than an “approved vendor” relationship? The answer may be no, which may be the correct answer. Do not try to convince yourself otherwise if the situation is not appropriate.

Deep owner-supplier relationships require a great deal of mutual effort to establish and maintain, but when they work, they are hugely rewarding for both sides. An integrator is assured of being paid fairly for work delivered without micromanagement, and the owner knows it can expect the best effort possible from the integrator. All projects are delivered with the lowest total cost of ownership, and the owner is assured of ongoing support to ensure gains made are preserved and encouraged. Such relationships are rare, but when they happen, all benefit substantially.

Paul J. Galeski, the chief executive officer and founder of MAVERICK Technologies, specializes in high-level operational consulting, as well as the development of automation strategy and implementation for automation technology. He is also involved in expert witness testimony, and is a contributing author to Aspatore Books’ Inside the Minds, a series of publications that examine C-level business intelligence.

A version of this article also was published at InTech magazine.