Manufacturing companies use a number of methodologies in an effort to improve the efficiency of manufacturing and improve delivery on customer requirements. These methodologies include initiatives like Lean, Six Sigma, and Theory of Constraint (TOC), with Lean and Six Sigma joining into the single initiative of Lean-Six Sigma (as a result of similarities in their methods). In addition, most (if not all) methodologies look to Design of Experiment as an integral part of these methodologies.

There are some differences in the methods, and depending on the particulars of the manufacturing company, one of these methods could be better than another for that specific company, and the suitability of any one methodology will change as the company’s manufacturing environment matures. The important thing to remember is that these methodologies are just a few of the many tools that can be used in manufacturing operations management (MOM), and over the entire history of a company, more than one of them could be used. Each of these methods has its benefits and its specific “goal” to be accomplished.

One common requirement of all these methodologies is that they all require data collection during production in an effort to characterize the process (or at least a segment of the process). In addition, they all also advocate comparing the outcome of an improvement initiative with the original process characterization to ensure that the expected outcome was achieved. To properly characterize a process, a key requirement is a large enough sample size for each improvement to ensure a good understanding of process characteristics.

The issue with sample size is that if the data collection is performed manually, it takes a lot of effort to collect that data. So much effort that most initiatives either use a limited amount of samples (possibly distorting the validity of the initiative) or the scope of the initiative is limited to a single operation (likely ignoring interactions between operations that may be relevant). In either situation, the outcome of any analysis performed on the data that was collected is highly likely to present skewed or completely misleading results. In the end, this will lead to a failure of the improvement initiative to achieve its expected results.

A book recently published by the International Society of Automation (ISA) called “MES: An Operations Management Approach,” discusses the issues of manual data collection and the effects on continuous improvement (CI) and in the wider scope of manufacturing operations management (MOM).

Manufacturing Execution Systems: An Operations Management Approach

Manufacturing Execution Systems: An Operations Management Approach

In the book, the authors Grant Vokey and Tom Seubert discuss the impacts of not achieving the initiatives goals, as well as the costs from the wider MOM perspective and the impact that manual data collection can have on how rapidly issues can be resolved when using quality initiatives like Lean, Six Sigma, and TOC.

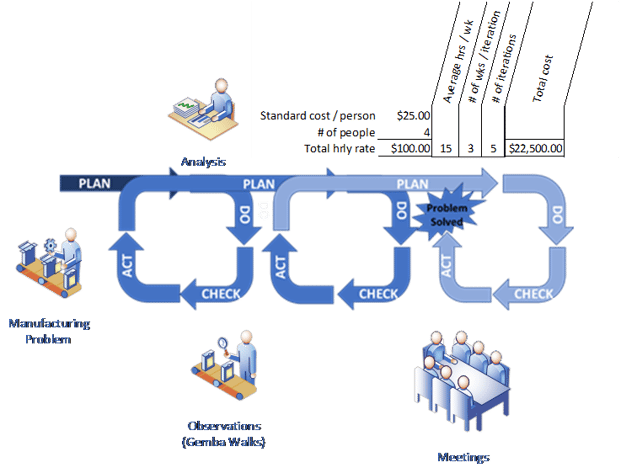

Regarding the cost impacts of continuous improvement, Vokey and Seubert present an example of a CI initiative using the very common Deming cycle of “Plan, Do, Check, Act.” This cycle is the basis of most initiatives where even the DMAIC cycle used in Six Sigma is simply an extension of the Deming Cycle. Vokey and Seubert point out that most activities, in using the Deming Cycle, will take multiple iterations of the cycle and multiple people to determine how to correct a problem. The cost of determining the correct solution to a problem can add up significantly with multiple iterations for the analysis and additional iterations for prospective solutions.

Figure 1: Cost example for a single improvement initiative

Figure 1: Cost example for a single improvement initiative

The cost associated with manually managing a CI program is also one of the primary reasons many companies do not maintain a formal program. This results in ad hoc initiatives that may not achieve their required goals and are highly unlikely to be sustained (i.e., the company will have a relapse of the issues within a short period of time).

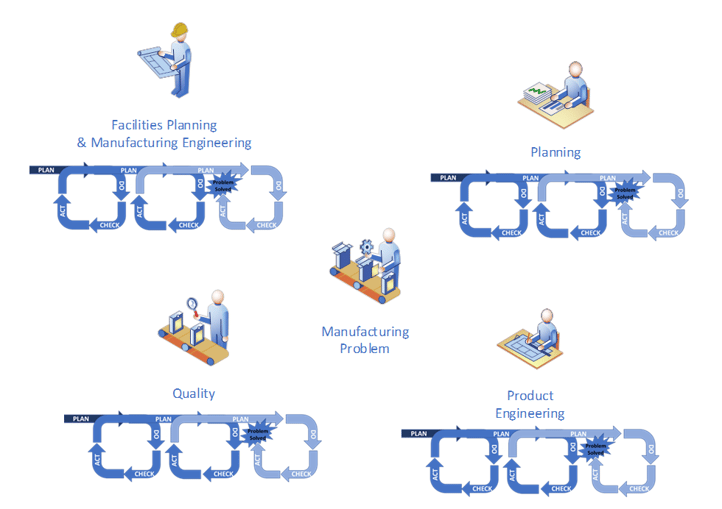

In the book, Vokey and Seubert also point out that each department within a company is performing (or should be performing) their own independent improvement initiatives, multiplying the costs even more. The authors show how automating the data collection process by using MES can significantly lower the cost of managing a CI program.

Figure 2: Example of multiple departments and independent analysis

Figure 2: Example of multiple departments and independent analysis

Within the book, the authors cover a wide range of subjects related to MOM and how using MES to support MOM initiatives can greatly lower the costs of managing a manufacturing environment. They take a deep dive into the use of MES as the central part of a continuous improvement management program.

In the chapters on “Quality and Traceability,” and specifically in the chapter on “Continuous Improvement: Benefits and Details,” Vokey and Seubert provide operational examples of the cumulative cost of problems to manufacturing and highlight the costs of ignoring these issues.

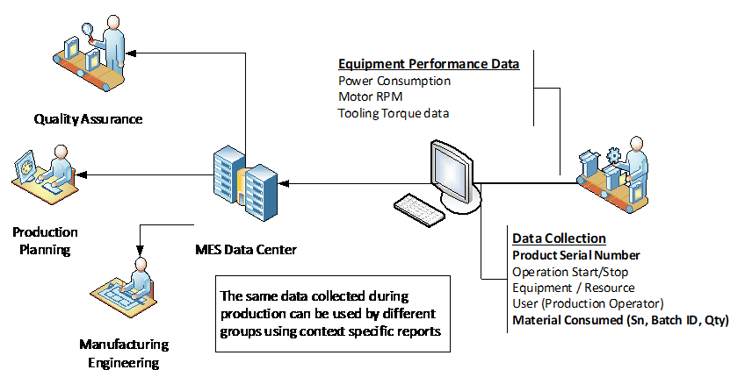

In most cases, many of the independent CI initiatives within a company will require the same data to analyze a problem, with the data only being reported in a different format.

Figure 3: Data collection is reformatted for the appropriate reporting requirements

Figure 3: Data collection is reformatted for the appropriate reporting requirements

As a tool for support of CI, the MES is invaluable. However, most companies are unaware of the value, as they’re usually also unaware of the cost impact (and hence profit loss) of unresolved manufacturing problems and poor management of a CI program. Automating the data collection for manufacturing is key to sustained improvement of manufacturing and reduction of the cost of MOM. Proper configuration of MES can be almost as important to CI as the management of the CI program itself.

To read an excerpt of this book or to purchase it from ISA Publishing, visit the ISA Store.