This article was written by Brian Batts, proposal and estimating group manager at MAVERICK Technologies, a Rockwell Automation company. Brian has more than 20 years of experience in automation, and has served in roles including systems engineering, lead engineering, commercial management, project management, account management, and consulting.

Although technical considerations are normally in the forefront as companies plan automation upgrade projects, cost is often the factor able to outweigh all others. All the wonderful ideas about new equipment will not go anywhere without finding the means to pay for it. Engineers may be able to calculate reaction rates or liquid velocities in pipes and tune the trickiest PID loops, but understanding the costing process for a major project often seems elusive.

To help make sense of it all, let’s look at how the cost for a major upgrade project in an existing plant gets put together. For the sake of argument, the scope will involve replacing an old distributed control system (DCS) with a more current platform. The plant in our example is a single location for a larger corporation with multiple facilities dispersed around the country and world.

Such an upgrade is often the most complicated kind of project, because much of the work is unpredictable. A greenfield installation is far more clear cut. Because it builds from scratch, cost estimating is simpler. A DCS upgrade is like fixing a plumbing problem in an old house—until you start looking inside the walls, you really do not know exactly what you will find.

Three-stage process

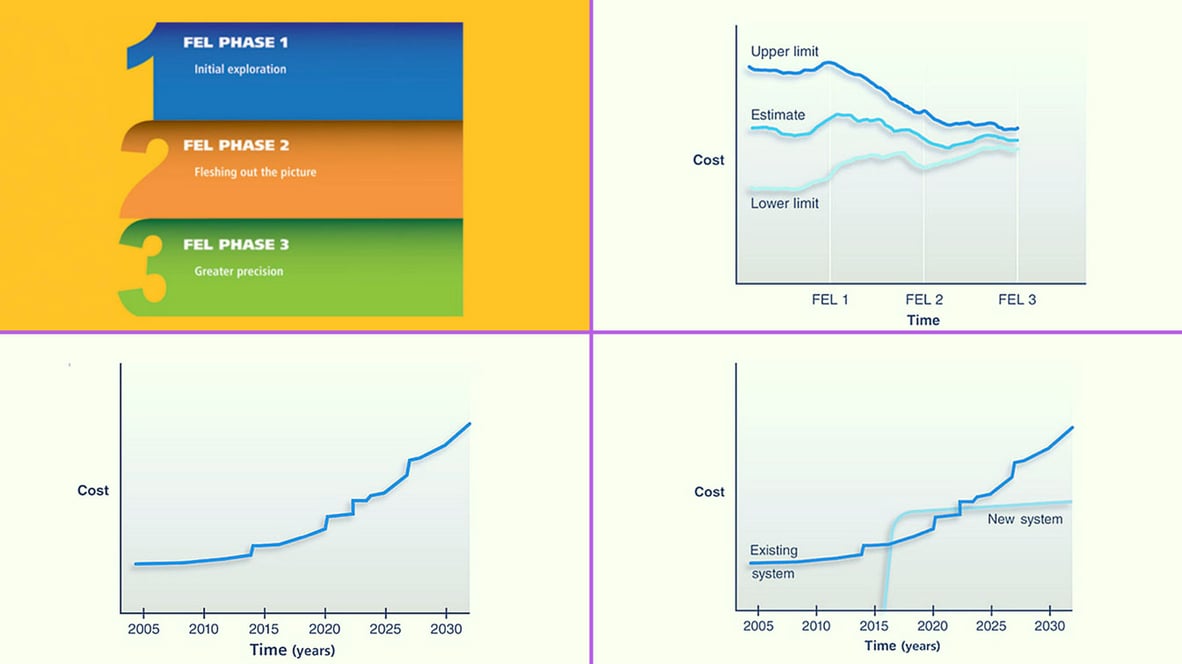

Planning is critical at all stages of projects because of the risks and costs involved. Poorly planned projects invariably take longer, cost more, and are less effective than well-planned projects. As a result, front-end loading (FEL) is important, because planning sooner is better than later. The same applies to costs. There are three distinct stages in the costing process, each with its own characteristics and expectations.

As a project moves from stage to stage, cost estimates become increasingly precise, but equally important, so do the technical details. The two move together through the process, and one really cannot be considered without the other. At the end of each stage, there is a decision—call it a toll booth or checkpoint—where progress either continues or stops.

A DCS upgrade project like the example discussed here usually originates at a local plant. The control system is no longer supported, and the plant manager has to deal with the possibility of failures complicated by an inability to find spares. The cost of maintaining the old system grows along with the risk of production interruptions, so the company needs to find a solution. Eventually, simply keeping the plant running consumes far too many resources.

However, at this point there may be no money budgeted for such an undertaking. The plant managers have to approach their “corporate” financial people to get the cash to make it a reality, and nothing will happen without having a sense of how much it will all cost. Somebody, internally or externally, has to come up with some numbers. Let’s look at the process, phase by phase.

FEL phase 1: Initial exploration

As a project idea is being launched, the most important questions to answer are:

- What systems need to be replaced?

- What parts of the production equipment will be touched?

- How might production be affected?

- What systems (safety, utilities, etc.) might be involved?

Adding a business-case justification at this point can be a major help. Documenting how much it costs to maintain the old system (costs that could be avoided if replaced) or the impact of outages on production is a plus.

Some companies try to do their own cost estimates at this point, or they might bring in a trusted consultant or system integrator to ensure they have covered all the elements. If the vendor for the new DCS is already selected in keeping with a company directive, a representative will typically offer an opinion and perhaps some numbers, but at this stage there will be few specifics.

In most cases, an FEL 1 price is simply a ballpark lump-sum figure. It is calculated using rules of thumb, such as $X per tag and a few other factors. It is not precise, usually plus or minus 50 percent, but it gives the corporate budgeting people something to work with. Time and money expended at this point are minimal (some internal time, a few meetings to discuss the scope, and possibly some hours of consulting time). Getting this far is not normally a costly proposition. When presented with the resulting cost estimate, the budgeting people will either say yes and give approval to move to the next phase of project evaluation or say no, the project is not going to happen at this time. There are a wide variety of reasons why a given project does not proceed.

FEL phase 2: Fleshing out the picture

The second phase is where things become much more specific. Risk goes up, because time and money expenditures increase, and decisions made are capable of shaping the facility and its operation for many years.

At this point, unless there is a specific policy directive in place, the main DCS platform provider has probably not been selected. Some companies use the same vendor in all plants, whereas others limit selections to a short list of options, perhaps two or three depending on the situation. In the absence of such directives, the choice may be wide open. This selection has a huge effect on the project and the years of operation thereafter, so it is very critical.

FEL 2 is where the technical evaluation of the project goes into much greater depth. All the stakeholders look at a piping and instrumentation drawing of the plant or unit and begin to draw the lines of what will be included in the project. If the diagram is complete and up to date, this should be straightforward. However, it can become problematic if the plant has changed over the years without documenting the modifications. This step often predicts the tone for the whole project.

Now the team assembling the estimate, internal engineers, consultants, and system integrators have to walk through the plant and determine:

- How well is the plant running now with its existing field devices?

- What do the cabinets look like?

- How accurate is the documentation?

- How are things wired?

- What condition is the equipment in overall?

- Is everything roughly the same age, or have parts of the plant been updated already?

- How clean are the control system code and human-machine interface (HMI) graphics, along with associated documentation?

These situational evaluations are combined with the needs, wants, and dreams of the stakeholders—all the things on the list of desired capabilities for the new system. These elements are used when assembling the request for proposal (RFP) for the DCS platform. The more specific it can be, the more precise the vendor’s price estimate will be.

Selecting a system supplier

The process of selecting a DCS supplier merits an in-depth discussion. However, as a brief bit of background, note that when called into such a decision, a variety of issues come into play:

- experience of the prospective vendors in the company’s industry

- capability of the platform to control the process as the company expects

- appropriate size and scalability

- suitability for the company’s technical strengths

- vendor’s stability as a long-term business

- positive experiences with the vendor on other projects

The evaluation should not fixate on price. In most cases, price eventually becomes an issue, but it should be a side discussion and not take primary importance. This will be a long-term commitment, so a short-term consideration, such as initial purchase price, should not drive the bigger picture. Total cost of ownership (TCO), which collects all the costs over the platform’s life, is a more important consideration—more on that later. Generally, during FEL 2, an RFP using the information collected during the evaluation will be issued to more than one DCS vendor, usually two or three. In most cases, the list of practical options regarding the choice of vendors can be winnowed down fairly easily.

When all the pricing information is collected, including the vendor quotes, the company can create a matrix of capabilities and options as part of a larger report on the entire project. If it is a sizeable project, such a report can be more than 100 pages. If done thoroughly for a large plant or process unit, the team putting it together can easily amass 1,000 hours or more. But the result is still an estimate. Although more precise than the FEL 1 number, it is typically plus or minus 25 percent.

The price from FEL 2 is characterized as total installed cost (TIC) and reflects the quotes from the DCS vendors in contention. It also includes:

- additional hardware

- software licenses

- functional specifications and definitions

- design-phase engineering

- field services, including configuration and factoring acceptance testing (FAT)

- commissioning and startup

- user’s internal support costs, including project management, staff participation in planning, and training

- ancillary third-party equipment

There will be a specific TIC associated with each DCS vendor in the running. The ancillary elements will change, because the exact scope will be different from vendor to vendor. Note that an experienced integrator will recognize the amount of work required to implement vendor C may be much less than vendor B.

Before purchase orders

All the activity so far has been designed to plan execution and provide an estimate. No orders have been issued, nor has any actual demolition or rebuilding taken place, and there is still a possibility the plant or company will simply decide not to proceed. This late in the process, complete abandonment is unlikely, but a project might be held off for a year or more. Moreover, the decisions of who gets assigned what responsibilities can also change. Nothing can be taken for granted.

If the project does proceed, regardless of who does what portion of the job, there is one unchanging element: the DCS vendor. Consultants, system integrators, and contractors can come and go, hired and fired as circumstances require. However, once the system is installed, the DCS vendor is there to stay. Of course anything can be changed, but the cost and amount of effort required would preclude such action in all but the most drastic situations, so vendor selection is extremely critical.

If a company is big and has installed systems from a vendor at multiple plants, it will have a lot of bargaining power with the vendor. However, if a company is smaller and has only one or two systems installed, the vendor may try to flex its muscles when it is time to talk about modifications to the system. An integrator who has watched these interactions firsthand can offer suggestions for how a company should work with a vendor.

FEL 2, while there are multiple vendors in the race, is the time for such negotiations. The vendor knows it is in the running and may be in a leading position, although the purchase order has not yet been issued. Now is the time to define the cost of a variety of things, such as:

- adding field devices

- modifying HMI screens

- adding new connectivity for remote access

- integrating a subsystem, such as fire and gas detectors

When the system is installed and operating, entering into these discussions will rarely be in the user’s favor. The extent to which different vendor companies press this issue varies, but all have done it at some time or another. When the time comes to ask for changes, it is important to have all these points nailed down, and an effective system integrator will help with the immediate negotiations and future strategies.

At the end of FEL 2

The company has now made a substantial investment to get a report with the level of detail appropriate for this phase, but the variability range is still plus or minus 25 percent. Whether from a consultant or a system integrator, a lot of hours have been billed, but there is no firm commitment to proceed to the full project.

Three things can happen: management can read the report and decide to do nothing (at least for some period of time); management may move to FEL 3; or the company may release the order. This is more likely to happen if the cost estimate is relatively modest and the company is comfortable with the DCS vendor and system integrator involved. The more the company trusts the participants, the less it will insist on getting the most precise estimate.

The company may take a do-nothing approach for a variety of reasons. The price may be more than it wants to spend; it may not currently have the money available; or it may prefer to invest its money elsewhere. Perhaps the company needs to reduce its overall manufacturing capacity, and it is deciding which plant to update while closing another. Such information supports critical decision making.

FEL phase 3: Greater precision

In most circumstances, the TIC plus or minus 25 percent from FEL 2 is not precise enough. It may be because the company’s accountants are exceptionally conservative or because of the size of the project, which might stretch over several years. A DCS migration across multiple units in a large process plant could be executed at a rate of one plant per year, so it is necessary to look ahead three to five years. The objective of FEL 3 is to narrow the TIC range to plus or minus 10 percent. It is still a range, however, and it can cost as much as FEL 2 to calculate.

FEL 3 begins with more concrete assumptions than the earlier two phases. For starters, the DCS platform is locked in place. There is no reason to leave in different options reflecting different suppliers. It is also time to plan in greater detail how the work will be executed, including coordination with production schedules and outages.

The company will also zero in on who will do what parts of the process. What will the DCS vendor provide? It will certainly provide the hardware, but how much software and to what extent will it be involved in the installation? Will there be a system integrator, and, if so, what part will it play? What internal resources are available?

Preparation of the FEL 3 estimate involves digging more deeply into the plant’s condition. Where technicians may have looked into rooms during FEL 2, now they are poking around in individual cabinets, looking at the condition of the cables. Does this cabinet need to be replaced? Moved? Consolidated with another? The magnifying glass now comes out to get down to the smallest details, which is why it is expensive to execute an FEL 3 evaluation.

With multiphase projects, FEL 3 estimates may follow the same phase-by-phase approach. If phase one has a go-ahead, calculate a final, detailed estimate so the company can release the order. Subsequent phases will be adjusted based on the initial experiences.

FEL 3 also looks farther down the road to refine the TCO with a more precise picture of the ongoing costs once the project has been executed and everything is in operation. The TCO, which combines the final TIC with expected additional costs over time, can be contrasted against the costs of keeping the existing system. This becomes the means to show how the project can save money in the long term.

Getting a go-ahead

A company may be driving an estimation project like this for a variety of reasons, from needing information for corporate decision making to a plant manager who simply wants better control and more reliable production. There are innumerable reasons why a specific project ultimately becomes reality or gets stuck on a shelf, but having an accurate cost estimate of the work involved and a detailed plan for execution goes a long way toward getting a green light.

Having the right resources, internal and external, ensures the development of a solid business justification for the project, supported by thorough plans and estimates with few surprises. When it is time to assign budget dollars to one plant or another, those factors matter and often determine a project’s fate.

About the Author

Brian Batts is MAVERICK Technologies’ proposal and estimating group manager. With 20 years of experience in automation, Brian has served in many roles, including systems engineering, lead engineering, commercial management, project management, account management, and consulting. Previously, Brian led numerous front-end loading projects providing planning and budgeting services to clients in various industries, including the specialty chemical, pulp and paper, power, and water/wastewater industries.

A version of this article also was published at InTech magazine.