The following insights are part of an occasional series authored by Greg McMillan, industry consultant, author of numerous process control books and a retired Senior Fellow from Monsanto.

Editor’s Note: This is Part 4 of a four-part blog series on smart automation of vessel heating and cooling. Click these links to read Part 1 or Part 2 or Part 3.

In this post I look at how the confusing unusual dynamics of a heat exchanger's temperature response in a recirculation line can be addressed by tuning and by the manipulation of a bypass flow. A simple additional PID is also offered to reduce heat exchanger fouling.

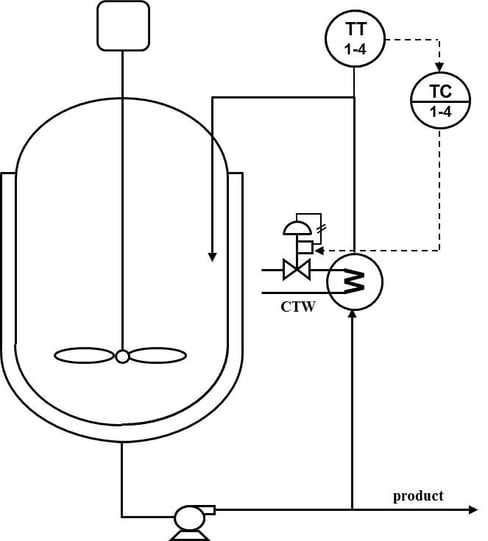

Heat exchangers in a process recirculation stream are used for vessel temperature control. The high velocities on the process side in the exchanger increase the heat transfer coefficient and reduce fouling. For cascade control the vessel temperature PID output is the setpoint of the exchanger outlet temperature (Figure 1). For the exchanger to do its job the recirculation flow must be high and a wide range of returning process temperature must be tolerated.

Figure 1 - Vessel process recirculation heat exchangers have a two stage temperature response that can confuse open loop tuning tests and users.

Figure 1 - Vessel process recirculation heat exchangers have a two stage temperature response that can confuse open loop tuning tests and users.

The response of the exchanger outlet temperature has a two stage response. The first stage is a response relatively fast self-regulating response of the exchanger. The second stage response is a protracted integrating response from the recycle effect of the process fluid in the vessel changing temperature. For large vessel volumes, the second stage response ramp rate is slow enough to allow fast exchanger temperature loop tuning based on the initial first stage response. Open loop tests that wait on the exchanger outlet temperature to settle out at a new operating point may be confused by the ramping from the second stage response. Practitioners may inadvertently tune for the second stage response rather than concentrating on having the PID quickly deal with the first stage response.

Insight: The goal is to make initial self-regulating first stage response much faster than the protracted integrating second stage response of the process recirculation temperature control loop.

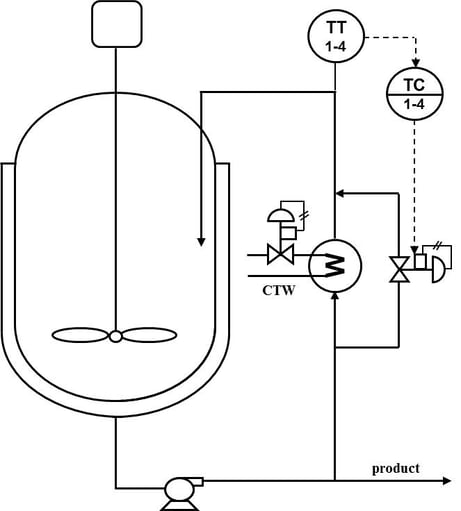

The speed of response of control of heat exchanger outlet temperature can be significantly increased by throttling a bypass around the exchanger and keeping the utility flow constant (Figure 2). This mode of operation bypasses the thermal lag of the heat exchanger. The response is as fast as the blending of the streams bypassing and going through the exchanger. Due to the change in heat transfer coefficient with velocity, there is an additional response from the change in heat transfer.

PID tuning for the initial response and manipulation of a heat exchanger bypass including a valve position controller to optimize the bypass valve position can eliminate the poor control from getting into the slow integrating process response and heat exchanger fouling and frosting. See Greg McMillan's ISA book Advances in Reactor Measurement and Control for an extensive view of practical opportunities for designing control strategies to achieve product quality and maximize yield and capacity in different types of fermenters, bioreactors, and chemical reactors.

Consider the response of the heat exchanger with cold water. An increase in cooling demand will cause a decrease in bypass flow and an immediate decrease in exchanger outlet temperature. The higher velocity through the exchanger will increase the heat transfer rate to the chilled water, making a further, slower reduction in temperature. If the measurement and the valve are fast enough, the PID can be tuned for a faster rate of response from blending providing further separation between the first stage self-regulating response and the second stage integrating response. Process recirculation heat exchanger bypass control provides a much faster secondary loop for vessel temperature control.

Insight: The response of a process recirculation heat exchanger outlet temperature can be significantly faster by throttling a bypass around the exchanger and keeping the utility flow constant.

Faster tuning of the secondary loop can compensate for utility temperature and pressure disturbances before they affect the vessel temperature loop and can help to prevent the protracted integrating response from recirculation. A faster secondary loop also makes the primary loop ultimate period faster, enabling more aggressive vessel temperature control and better compensation of process disturbances (e.g. feed temperature and concentration).

Insight: Faster tuning of the secondary temperature loop make both secondary loop and the primary vessel loop faster and eliminates the complications of the protracted integrating response from recirculation. The throttling of a heat exchanger bypass enhances this opportunity.

Figure 2 - The throttling of a bypass flow around the process heat exchanger provides a much faster initial response that provides separation of the first stage self-regulating and the second stage integrating responses.

Figure 2 - The throttling of a bypass flow around the process heat exchanger provides a much faster initial response that provides separation of the first stage self-regulating and the second stage integrating responses.

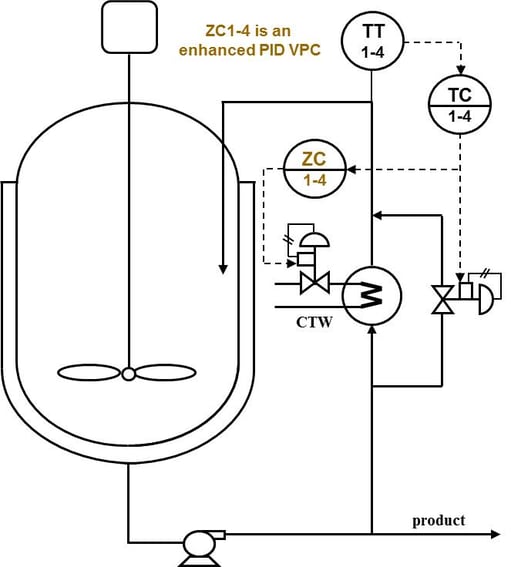

At low cooling or heating requirements, the hot or cold utility valve can be throttled to extend the rangeability of the exchanger. A valve position controller (VPC) can be used to prevent the bypass valve from going wide open by cutting back on the utility flow (Figure 3). A VPC can increase the turndown of the heat exchanger bypass control and prevent the process velocity through the exchanger from going below a minimum, thus reducing the degree of fouling and frosting. This minimum flow also keeps the process side heat transfer coefficient from dropping too low. A low output limit on the VPC can be used to prevent fouling and deterioration of the heat transfer coefficient on the utility side. The VPC should be the enhanced PID to minimize interactions by enabling the use of directional move suppression and eliminating the limit cycles from valve backlash.

Insight: A valve position controller can increase the turndown and efficiency of heat exchanger bypass control.

Figure 3 - A valve position controller can reduce fouling on the process side and extend the turndown of the temperature loop.

Figure 3 - A valve position controller can reduce fouling on the process side and extend the turndown of the temperature loop.

Tune the PID for a fast reaction to the initial self-regulating response of the heat exchanger in a process recirculation stream. Manipulate a heat exchanger bypass flow to eliminate the heat transfer lags of the heat exchanger giving a much faster response from a simple blend of bypass and heat exchanger process flows. Use a valve position controller to push a utility valve to a minimum throttle position increasing the velocity of the process through the exchanger, decreasing the fouling on the process side.

About the Author Gregory K. McMillan, CAP, is a retired Senior Fellow from Solutia/Monsanto where he worked in engineering technology on process control improvement. Greg was also an affiliate professor for Washington University in Saint Louis. Greg is an ISA Fellow and received the ISA Kermit Fischer Environmental Award for pH control in 1991, the Control magazine Engineer of the Year award for the process industry in 1994, was inducted into the Control magazine Process Automation Hall of Fame in 2001, was honored by InTech magazine in 2003 as one of the most influential innovators in automation, and received the ISA Life Achievement Award in 2010. Greg is the author of numerous books on process control, including Advances in Reactor Measurement and Control and Essentials of Modern Measurements and Final Elements in the Process Industry. Greg has been the monthly "Control Talk" columnist for Control magazine since 2002. Presently, Greg is a part time modeling and control consultant in Technology for Process Simulation for Emerson Automation Solutions specializing in the use of the virtual plant for exploring new opportunities. He spends most of his time writing, teaching and leading the ISA Mentor Program he founded in 2011.

Gregory K. McMillan, CAP, is a retired Senior Fellow from Solutia/Monsanto where he worked in engineering technology on process control improvement. Greg was also an affiliate professor for Washington University in Saint Louis. Greg is an ISA Fellow and received the ISA Kermit Fischer Environmental Award for pH control in 1991, the Control magazine Engineer of the Year award for the process industry in 1994, was inducted into the Control magazine Process Automation Hall of Fame in 2001, was honored by InTech magazine in 2003 as one of the most influential innovators in automation, and received the ISA Life Achievement Award in 2010. Greg is the author of numerous books on process control, including Advances in Reactor Measurement and Control and Essentials of Modern Measurements and Final Elements in the Process Industry. Greg has been the monthly "Control Talk" columnist for Control magazine since 2002. Presently, Greg is a part time modeling and control consultant in Technology for Process Simulation for Emerson Automation Solutions specializing in the use of the virtual plant for exploring new opportunities. He spends most of his time writing, teaching and leading the ISA Mentor Program he founded in 2011.