This guest blog post was written by Matt Sigmon of MAVERICK Technologies.

Many distributed control systems (DCS) in process plants are approaching the end of their useful lives, forcing facilities to migrate from an old DCS to a modern automation system. Although these migration projects require significant investment, funds spent can often be recovered quite quickly through savings from improved operations, less downtime, and decreased support costs.

To quantify the migration issue, consider that many process plants in developed countries are more than 50 years old. A large number of these plants have been controlled by the same automation system for more than 30 years. Many of these automation systems are of the DCS variety, although more recent vintage systems based on programmable logic controllers (PLCs) are also becoming obsolete.

A recent study estimates there are $65 billion of obsolete automation systems installed worldwide. If one assumes that a third of those are DCS-based, then more than 10 million DCS input/output (I/O) points will need to be updated over the next decade. Those sobering numbers illustrate the worldwide scope of the problem, but of course each plant and automation system is different, as is each DCS migration project.

The first step in any DCS migration project is to ascertain if migration is in fact required, followed by selection of the right partner. Justification is then required to determine rough costs, secure internal buy-in, and obtain funding. The final steps are project execution and long-term support.

This article will show you how to execute these steps and will include a case study example that shows how one process industry company successfully migrated from an older DCS to a new automation system.

Is it time to migrate?

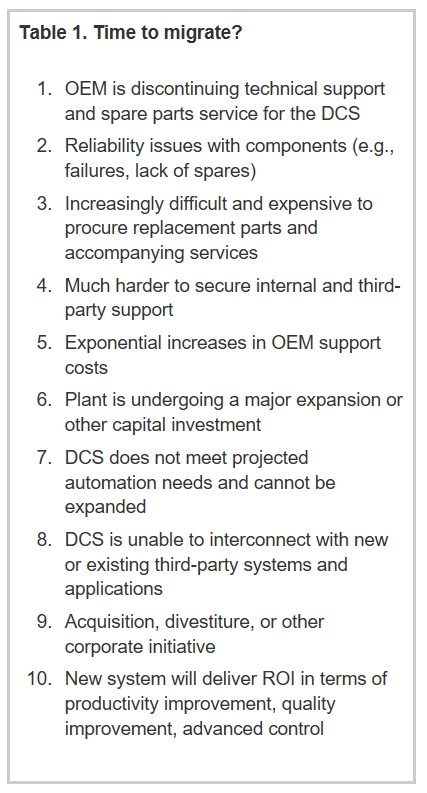

There are multiple reasons to migrate, as summarized in table 1. The most obvious for many older DCSs is obsolescence, a subjective term that can be stated objectively by examining existing support requirements.

If the automation original equipment manufacturer (OEM) has discontinued support or is likely to do so soon, then migration should be strongly considered, particularly if the DCS is becoming less reliable and failing more often. When support is discontinued, spare parts become increasingly difficult to procure, reducing options to scouring eBay or repairing decades-old components, both risky and expensive choices.

When an automation OEM discontinues support, it is usually because the DCS is decades old and because replacement components can no longer be procured or manufactured. In these situations, it is often increasingly difficult to find internal personnel to support such systems, leaving many a plant to rely on a single employee who is near retirement age for the operation of its entire facility.

OEM support personnel will also become increasingly unavailable, as will third-party providers, such as system integrators. And even when third-party support for a discontinued DCS is available, it is likely to be expensive, with costs often increasing at a near exponential rate.

Obsolescence is perhaps the leading and most obvious reason to migrate, but other reasons can be even more compelling. For example, the DCS may not meet projected automation needs, making it the limiting factor for plant capacity increases or additions to the product mix.

In other cases, the DCS cannot easily interface to new or existing third-party systems and applications. Workarounds for interface issues are either labor intensive and prone to error (i.e., manual data transfer) or very costly, risky, and time-consuming (i.e., development of custom communication interfaces).

When a distributed control system cannot interface to a third-party system in a suitable manner, then it cannot provide the requisite data to manufacturing enterprise systems, enterprise resource planning, and other business layer systems, and it cannot receive commands from these systems to change production schedules-negating much of the value of the automation and information systems.

Acquisitions and divestitures are also a fact of life in the process industry, and these trends show no sign of abating. When a new plant is brought into an existing fleet, it often makes sense to migrate the DCS to match the automation systems of the other plants, as this can allow a company to standardize operations and greatly reduce automation system operation and support costs.

The most difficult factor to quantify when deciding whether or not to migrate is the projected savings from improved operations delivered by implementation of features in the new automation system. For example, the new automation system may have built-in advanced control capabilities that allow plant personnel to greatly improve upon existing PID-based loop control.

If advanced control can allow operation closer to set point by a few percentage points on critical loops, the savings in increased production, better quality, lower raw material usage, and reduced energy consumption can be substantial.

Finally, a new automation system can often improve safety and cut downtime through more effective and advanced abnormal situation management, including enhanced alarm handling, incident diagnostics, and operator graphics that adhere to modern human-machine interface standards-all of which provide operators with the capability to either anticipate problems before they occur or to react more quickly and with greater effectiveness to incidents.

If examination of these factors results in a decision to migrate, the next step is selecting the right partner.

Picking the right partner

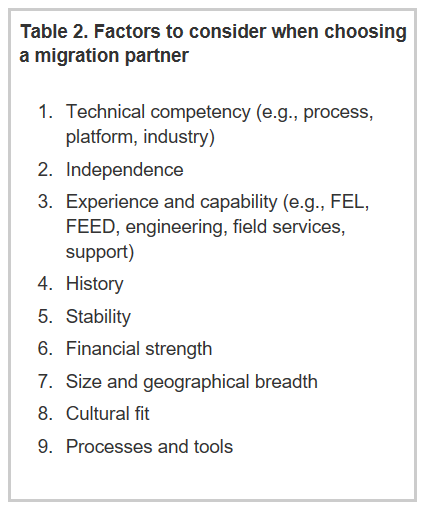

For a DCS migration project, process companies and plants will generally select one of three types of partners: an OEM vendor, a system integrator, or the system integration division of an engineering firm. The leading factors to consider when selecting a partner for DCS migration are listed in table 2.

First and foremost is technical competency, which must include domain knowledge of the particular plant and its processes. Domain knowledge can be easily determined by interviewing the partner's proposed project team leaders, and by speaking to customer references, particularly in the same or a similar industry. Domain knowledge varies widely among OEMs and integrators, with different prospective partners having specific strengths and weaknesses.

If sufficient domain knowledge is present, then the next step is to determine if the partner has experience with the types of automation systems typically applied to the plant's processes. This step can be simple if the automation system brand is predetermined, but is much more complex if the vendor has yet to be selected. When the vendor is not yet known, the selected partner should be an integrator or an engineering firm, as both will bring independence to the vendor-selection process.

Once a company selects the automation vendor, it can ascertain the partner's level of technical competency with the particular platform. An OEM will have a high level of expertise with its own products, but care should be taken if extensive interface will be required to applications provided by other vendors. Prospective system integrator partners must be examined to determine their level of technical competence with the selected vendor platform.

In some cases, an integrator may have greater capabilities and real-world competency with a specific platform, and it should not be assumed that the OEM is the best or only entity capable of engineering and commissioning the new system.

The migration project will also require a range of services starting with front end loading (FEL) and continuing to front end engineering design (FEED), project execution (including both engineering and installation services), and long-term support. The selected partner should be able to demonstrate expertise in all of these areas through work performed in plants with processes similar to yours.

Large OEM vendors are generally quite stable and have a long history of operation, making them reliable. System integrators and engineering firms should be examined more closely in this area, as many smaller firms may not have the required staying power, nor the required geographical reach and technical depth. Consider the initial and long-term support costs of these choices.

It is important to pick a partner for the project that is neither too big nor too small. If the partner is too big, as with a mega-engineering firm, your project may be assigned to a junior team, while the best and most experienced personnel are busy with very large projects. If the partner is too small, it can be stretched to the breaking point.

Many process industry firms have a fleet of process plants, and the selected partner should have the required geographical coverage, with an office within a reasonable distance of each plant.

Another important factor to consider is cultural fit, both at the executive and project team levels. If your company likes to make decisions quickly and execute projects to tight timelines, then your selected partner should have a similar corporate culture. If your company prefers to study all options in detail before proceeding carefully and deliberately, then your partner should share the same values.

Finally, the partner's specific processes and tools for executing migration projects should be examined. If these processes and tools are not well-defined and in place, it usually indicates a lack of experience with migration projects, a haphazard approach to project execution, or both.

The right partner will provide assistance with every step of your distributed control system migration project, starting with cost justification.

How to justify migration costs

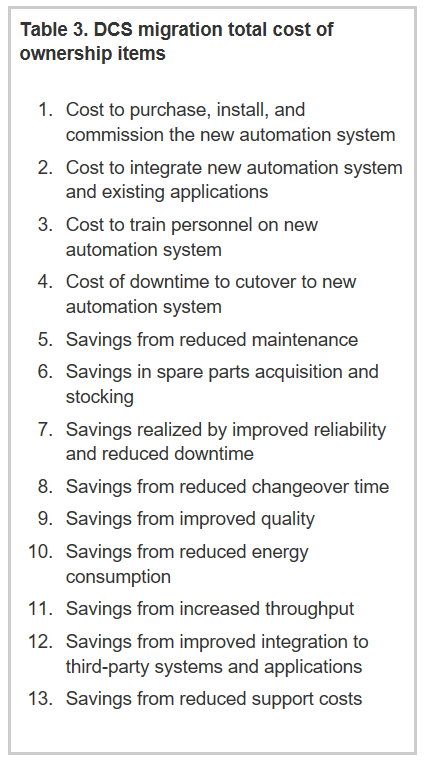

Justifying the costs associated with a DCS migration requires financial data that shows a positive financial benefit when total life-cycle costs and benefits are considered. These total life-cycle costs and benefits are often referred to as total cost of ownership (TCO). They can be calculated by putting dollar figures to the items listed in table 3 and by quantifying other items specific to the particular plant.

The first four items in table 3 are costs associated with purchasing, installing, and commissioning the new system. The bulk of these costs can be estimated by comparing migrations at similar plants. Third-party partners such as OEMs and integrators can be valuable sources for this cost data.

The remaining items in table 3 are projected savings. They are generally much harder to calculate than cost items, because savings are very different from plant to plant depending on myriad factors led by the condition of the existing DCS.

Migration without downtime

Ripon Cogen LLC owns and operates gas-fired cogeneration plants in Ripon, Calif. The balance-of-plant (BOP) equipment at one of its plants was controlled by an outdated DCS. The main BOP equipment that needed to be migrated to a new automation system were the heat recovery steam generator, de-aerator and feed water system, gas compressor system, compressed air system, and water treatment plant. The non-BOP turbine control, water distiller, and ammonia chiller also required migration.

This cogeneration plant migrated from an older DCS to a modern automation system, alleviating support issues and increasing uptime.

This cogeneration plant migrated from an older DCS to a modern automation system, alleviating support issues and increasing uptime.

Migration was required because the existing DCS had serviceability issues, excessive downtime, and decreasing hardware availability. The DCS used a proprietary operating system and networks with no vendor support, which made it very expensive to replace the failed historian server and to add desired features such as automated report generation.

Ripon used the services of a system integration firm to perform an analysis of the existing control system, which primarily consisted of Westinghouse WDPF controllers and I/O and Wonderware human-machine interfaces.

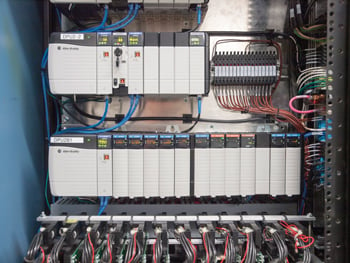

Engineers analyzed the existing system, developed a functional specification, and worked with Ripon's operation and maintenance staff to take a fresh look at plant operations. They then developed a functional specification for the new automation system based on the Rockwell Automation PlantPAx. A plan was also developed to integrate the existing Wonderware human-machine interface applications for the turbine control, chiller, and distillation plant into the new automation system.

The system was selected for a number of reasons including open control networks, hardware availability in nearby cities, and the capability to replace the existing controllers and I/O with new components with little or no disruption to existing operations. Other key system features important to this application were Microsoft desktop and server operating systems, a world-class historian server, and I/O capable of communication with HART smart transmitters.

As with most migration projects, maintaining uptime during the cutover from the DCS to the new automation system was critical, so engineers analyzed the existing DCS hardware and developed a low-risk hardware replacement plan.

The existing redundant processor drops were replaced with redundant processors using device-level ring for I/O communications. Westinghouse Numa-Logic I/O was replaced with new I/O and new wiring from I/O cards to field termination blocks. Westinghouse Q-Line I/O was replaced with new I/O using custom interface cables between existing QLine I/O swing arms and new I/O cards. This migration path left all existing field terminations intact, which greatly reduced wiring issues during the cutover phase of migration.

The project was successful as the plant experienced no unscheduled outages during the migration process, and the facility started up on schedule and was ramped up to full power on the first day of operation. Going forward, the plant has experienced fewer outages due to the improved automation system.

Many modern automation systems provide wiring components that allow existing field terminations to remain intact, allowing quick cutover from the old to the new I/O.

Many modern automation systems provide wiring components that allow existing field terminations to remain intact, allowing quick cutover from the old to the new I/O.

For example, if the existing DCS is obsolete with high maintenance and support costs, then the savings in these areas will be significant. If DCS migration is being driven by other reasons, such as improved performance and reduced downtime, then these items will be of more relative importance.

To estimate these costs and savings, a thorough FEL process should be followed to develop detailed scopes, schedules, and budgets. The FEL results will yield the required TCO estimates, which should result in a positive return on investment (ROI) when all factors are considered.

Completing a thorough financial analysis, including TCO, is the key step to garnering internal approval, and once this approval is granted, then project execution can commence. One DCS migration project progressed from justification to successful execution, using much of the methodology described in this article.

DCS migration projects are major undertakings that will affect the operation of an entire plant. Proper execution of these projects is critical if the plant and the process industry firm are to remain competitive. Selecting the right partner can provide assistance every step of the way, from justification to execution to long-term support.

About the Author Matt Sigmon is director of DCS Next at MAVERICK Technologies. Matt joined the firm in 2005 when the company acquired General Electric Automation Services, where he had worked since 1997. He has served as director of sales operations, regional manager, engineering manager, project manager, and engineer. Sigmon now directs the company’s DCS Next initiative. He earned a bachelor's degree in chemical engineering from Clemson University.

Matt Sigmon is director of DCS Next at MAVERICK Technologies. Matt joined the firm in 2005 when the company acquired General Electric Automation Services, where he had worked since 1997. He has served as director of sales operations, regional manager, engineering manager, project manager, and engineer. Sigmon now directs the company’s DCS Next initiative. He earned a bachelor's degree in chemical engineering from Clemson University.

A version of this article also was published at Intech magazine.